Waves of heavy rainfall in early December 2025 spurred landslides and flooding in parts of the Pacific Northwest. The deluge was the result of a potent atmospheric river that took aim at the region starting around December 7.

Atmospheric rivers are long, narrow bands of moisture that move like rivers in the sky, transporting water vapor from the tropics toward the poles. They occur around the planet, most often in autumn and winter, with the U.S. West Coast typically affected by moist air that originates near Hawaii. In this event, however, some of the moisture arrived from even farther away, originating roughly 7,000 miles (11,000 kilometers) across the Pacific from near the Philippines.

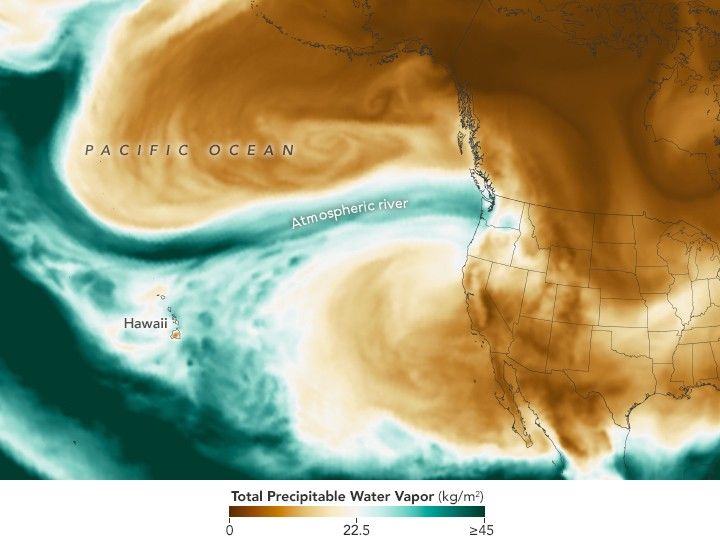

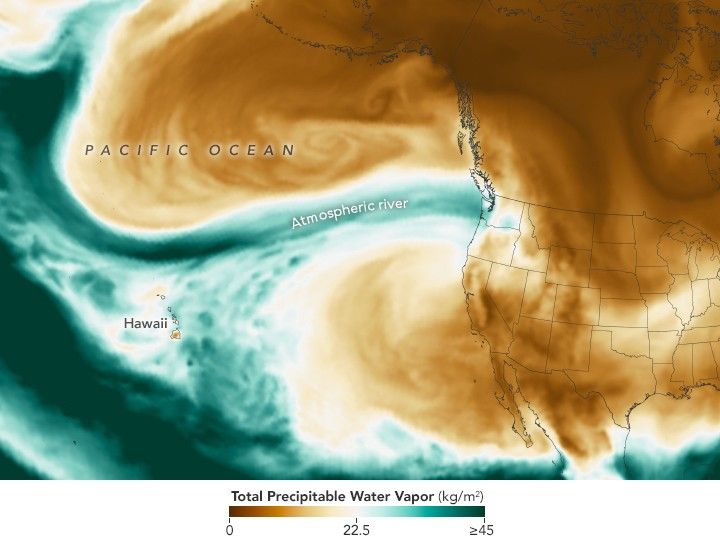

This map shows the total precipitable water vapor in the atmosphere at 11:30 p.m. Pacific Time on December 10. It is derived from NASA’s GEOS (Goddard Earth Observing System) and uses satellite data and models of physical processes to approximate what is happening in the atmosphere.

Precipitable water vapor represents the amount of water contained in a column of air, assuming all the water vapor condensed into liquid. The map’s green areas indicate the highest amounts of moisture. Note that not all precipitable water vapor falls as rain; at least some remains in the atmosphere. Nor is it a cap on how much rain can fall, since rainfall can increase as more moisture flows into a column of air. Still, it serves as a useful indicator of areas where excessive rainfall is likely.

According to the National Weather Service, preliminary ground-based measurements showed that several locations in western Washington received more than 10 inches (250 millimeters) of rain over a 72-hour period ending on the morning of December 11. Seattle-Tacoma International Airport set a daily rainfall record on December 10, with 1.6 inches (40 millimeters).

River flooding was ongoing on December 11, with the Skagit River and Snohomish River seeing record or near-record flood levels that day. Floodwater and mudslides have closed numerous roadways, including the eastbound lanes of I-90 out of western Washington.

NASA’s Disasters Response Coordination System has been activated to support the ongoing response efforts by the Washington State Emergency Operations Center. The team will be posting maps and data products on its open-access mapping portal as new information becomes available.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using GEOS data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA GSFC. Story by Kathryn Hansen.

References & Resources

- Cliff Mass Weather Blog (2025, December 8) The Torrent Has Begun: The Philippine Connection. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- National Water Center, via X (2025, December 10) Key Messages for Pacific Northwest Flooding. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- National Weather Service (2025, December 11) Miscellaneous Hydrological Data. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- NOAA (2025, February 21) What are atmospheric rivers? Accessed December 11, 2025.

- USA Today (2025, December 11) Catastrophic flooding sparks evacuations in Washington state. See forecast. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- The Washington Post (2025, December 8) A 7,000-mile atmospheric river is stretching from Philippines to the U.S. Accessed December 11, 2025.